It was something of an apology in the form of an honor, an anemic effort to make up both for that dispossession and for the recent removal of what so many thought was the Indian on the penny. Probably the word “Liberty” embossed on the coin’s edge suggested that the Native American, though clearly male, was another version of the classical goddess.

But he lasted only until 1938 when the coin’s 25-year legal term was up. He was replaced ironically by no less a dead white male CEO than Thomas Jefferson, the same Liberty-loving republican who had written the charge-sheet against King George in 1776, who had, as Secretary of State in the 1790s, approved the design of the first flowing-hair Liberty coins and turned his Department to favor king-executing revolutionary France, and who had become the first President of the party he founded and named “Republican.” Jefferson is still on the nickel, a tenure any monarch would envy, though an antipathy to single executives lies behind much of his career.

Next to go was Liberty on the quarter dollar. The first quarters’ Liberty was a draped bust in 1796. The bust’s hair was capped in 1815. Liberty was seated in 1838 (with her name, “Liberty,” in very small letters across her shield), but returned in 1892 by the designer Charles Barber to a stern-faced profile bust wearing a Phrygian Liberty cap wound round with a laurel victory wreath.

On the front of the cap the title, “Liberty,” appeared in tiny letters which wore off quickly, but no one seems to have wondered who she was. In 1916, she was represented for the first time standing, with her title relegated to the coin’s rim with “In God We Trust” visible on her pedestal. Standing Liberty was dressed décolleté holding a simple shield until 1917 when modesty and the Great War seemed to demand the addition of an armored breastplate.

This Liberty lasted until 1932, when George Washington himself replaced her in celebration of his 200th birthday. Washington, like Jefferson, is still there too.

Next to go after the quarter was Liberty on the dime, but not exactly. On the first U.S. ten-cent piece in 1796, her hair had been unbound but her bust draped. In 1809 her hair was capped.

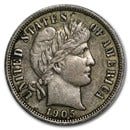

She was seated in 1837, but was returned by designer Barber to the profile bust with the Liberty cap and laurel wreath.

This Barber Liberty head, like the one on the quarter, wore her title, “Liberty,” in even tinier letters on her headband, but again, no one seems to have doubted her identity.