Real Persons on Coins:

Ominous Precedents and a Paleofeminist Plea

In December, 1978 (how very long ago that was) there was much talk of the coining of a new dollar with the great suffragist leader, Susan B. Anthony on the obverse, replacing President Dwight Eisenhower. Congress had advised the Mint, and the coin had been struck and circulated; but it was not, in the end, going to please. In December, Representative Margaret M. Heckler, a Reagan Republican from Massachusetts who had favored the Anthony dollar, summed up a strong current of opinion by saying that the likeness of Susan B. Anthony on the new coin had replaced that of “a mythical figure, which means nothing to anyone,” [NYTimes, Dec. 14, 1978, p. A18].

That mythical figure means something to me, though. I wrote to the Times about her. [NYTimes, Dec. 26, 1978, p.18] Did Representative Heckler know she was Liberty?

Liberty, say many disdainful feminists, is not a “real” person. Well, she is indeed mythical, but myth has powers that can cost us if we neglect them. Liberty was a goddess and she is one still. (Perhaps the opposition to her is religious—Heckler was Catholic.) The Founding Fathers—we fans of Abigail Adams say “Founders”—decided that once their new 1789 Constitution went into effect with its ban on states coining money, that they would put a portrait of Liberty on the first coins of the new United States of America, and with a law passed in 1792, they did. They knew they had done something new and were in the market for memes. “A New Order of the Ages” and “Out of Many, One,” in ancient Latin, were chosen for the Great Seal. The old imperial eagle seemed a more unifying symbol than the American turkey. The flag that flies everywhere now was not yet official; but Liberty was even more obvious.

Why? Because Liberty had been a symbol since antiquity of that uncommon and somewhat confusing system of government in which power is distributed over several officeholders instead of just one and in which the officeholders with the most power are elected as opposed to being appointed by another officeholder. Seemingly incompatible with a chain of command, it’s still an idea that’s hard to grasp. We call it by a Roman term, “republic,” res publica, or “the public thing.” The Romans had one of those. They got it after they expelled their kings in 509 BCE, and went to a hereditary but meritocratic Senate and a much less aristocratic committee of the tribes (Comitia Tributa). This Roman Republic lasted a long time; but like most republics it eventually got trapped in its own contradictions, including massive imperial expansion, wealth inequality, and civil war. Monarchy was reestablished in Rome some 450 years later under one old name, “dictator,” and several new ones like “victorious general” (Imperator or emperor), “first citizen” (Princeps or prince), “heir of the dynasty” (Caesar), and “highly honored one” (Augustus).

And the Romans had a coinage. Roma, the goddess of the city, was on most coins. They never put the head of a “real person,” least of all a live one, on a coin because that act would have been both sacrilegious and unrepublican. Even Sulla the dictator had not put his face on a coin. But the dictator Julius Caesar did, and after that it was all emperors. (“Is it lawful to pay taxes to Caesar?” Jesus was asked, and replied, “Show me a coin.” Indicating Caesar’s head on it, he said, “Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s.”) On other Roman Republic coins was another goddess, Minerva, Rome’s warrior goddess of wisdom. That is interesting because Minerva’s meme was almost identical to that of the Greek goddess Athena, who had graced the coins of king-free Athens since before Rome became a republic.

The first “real persons” to appear on Greek coins were the Kings of Macedon. After King Alexander the Great, the Greek city-republics never really recovered their independent republican government. As for the first “real person” to appear on the coins of Rome, that was Julius Caesar, and there, too, republican government ended. Republics ever afterward have usually been careful to keep real people off their coinage, especially real people who are still alive, and to re‐acquaint each succeeding generation with the maxim that in a state ruled by more than one person nothing—least of all its coins, perhaps the nation's most powerful advertising medium—should promote the idea of monarchy.

The United States was founded as a federated republic of republics. State laws were made for each state by its collective legislature and executed by executives that, even when single, were well-trammeled by checks and term limits. The United States itself fought the six years of Revolution and spent the first four years of peace under a legislature called The United States in Congress Assembled, composed of a delegation sent by each state, with each delegation having only one vote. The chairman elected by this super-legislature to preside over its debates was titled “President of the United States in Congress Assembled.” That and a bunch of standing Committees was the nearest thing we had to a chief executive.

In 1776, this assembled Congress adopted the resolution of a delegate from Virginia, Richard Henry Lee, elaborated by a Congressional Committee of that Congress and written by a Committeeman, Thomas Jefferson, which blamed the King of England for all the grievances of the American colonies in a single Declaration of Independence. Republicans in New York, where the Declaration was first read out to Congress’s Army by its Congressionally appointed commander, George Washington, replied to it by pulling down the statue of King George at the Battery in Manhattan and melting it into bullets. (In 1793, the French republicans would take the American example considerably further, having captured their actual King trying to escape to an enemy country, they severed his actual head from his body.)

Congress’s army unexpectedly won the war with the King of England—on aid from the King of France, from the United States of the Netherlands and from loans the states took out. But Congress could tax the whole country only by a unanimous vote, its paper money was inflated to worthlessness, and interstate commerce was a maze of state tariffs and customs. A convention of Founders who wanted stronger national government assembled in Philadelphia to produce one, the Constitution. After the states voted one by one to ratify it between 1787 and 1788, it went into effect in 1789, and soon the United States had both national taxes and a national bank and was ready with a law to put Liberty on a national coinage.

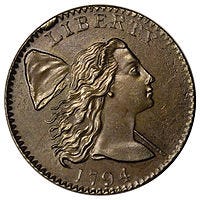

The new government began minting in 1793 with a copper penny, the “Large cent.” There was nothing on its obverse but a profile bust of Liberty with her face set, her neck bare and her unbound hair flying back as if she was facing to the right into a gale. There was no place to put her name on her clothing, because no clothing was evident. In the absence of even a tattoo, her title “Liberty,” was engraved in relief on the rim of the coin above her head.

To make her more unmistakable in 1794 they accompanied her bust with a staff topped with a “Phrygian bonnet,” the Liberty cap of the freed Roman slave.

French revolutionaries had executed their king in January, 1793, and there as in America Liberty was portrayed with a Roman freedman’s Liberty cap as a republican revolutionary.

Liberty, the rebel woman with her bare neck and gloriously windblown hair on the first U.S. cent and half-cent (1793-97) was slowly made more modest and decorous on later cents, and by degrees less revolutionary. In 1800 her bust was draped (1800-1808); from 1809 to 1836 her windblown hair was bound by a fillet; in 1840, no longer flowing, it was braided and bound by a coronet (1840-57). Much the same progression toward Order was made by Liberty on the large cent, but her coronet came earlier (1816-1839); and the same progression could be seen on the larger denominations.

In 1797 Liberty on the high denomination gold coins began wearing her hair wound into a cone-shaped topknot. Other symbols, shields and eagles, were used on circulating coins, but rarely without Liberty. “In God We Trust” first appeared in the middle of the Civil War, and stayed on the nickel until 1883. (It was required on all coins by law in 1908, and went on paper money during the Eisenhower administration, when the dollar was the only circulating coin left with Liberty on it.)

It was 1909, when Liberty was first removed from a U.S. circulating coin, and the coin was the mass-circulation penny. Liberty had been on the one-cent piece since 1793, but the version of Liberty used on the penny since 1859 (and on the $10 gold piece since 1907) had been “American Liberty,” Liberty with a feathered headdress.

Her title, “Liberty,” had been engraved on the penny’s headdress band but it was very small and in such low relief that it wore off quickly and by 1909 Americans had all agreed to call it the “Indian Head” penny. The replacing of American Liberty with the first Republican president, Abraham Lincoln, was a project for Republican President Theodore Roosevelt, partly as a way of cementing the victory of the Republican Party, the Union, and reunification in the Civil War, and partly to evade responsibility for what had been done to the American Indians in his lifetime. In 1886 Roosevelt had given a speech in South Dakota, amending the opinion of the Indian fighter General Sheridan: “I don't go so far as to think that the only good Indian is the dead Indian, but I believe nine out of every ten are, and I shouldn't like to inquire too closely into the case of the tenth. The most vicious cowboy has more moral principle than the average Indian.” Thus, by 1909, not only had Liberty been confused with an Indian, the Republican Party had begun to forget what a “republic” was.

Lincoln’s was the first portrait of a dead, white male CEO to appear on a circulating U.S. coin. As we all know, it was not the last. Real men have been pushing the Republic’s representative woman off our coinage ever since. The next Liberty to go was the one on the nickel (half-dime), in the 1830s a soldierly goddess

In 1913, the first year of Woodrow Wilson’s new Democratic administration, a genuine American Indian replaced her, accompanied on the reverse with an American bison. The designer, James Earle Fraser, rejected any identification of that Native American’s tribe or people, insisting he had conflated at least three male models from the Kiowa, Cheyenne and Sioux. (The model for the buffalo turned out to be in captivity in the Bronx Zoo.) It seems not to have been noticed by journalists of the time, but the new head on the nickel represented very well the vexed relationship of the first Americans with the later immigrants who had so recently dispossessed them of the West.

(Part two also on Substack)